Tips for Creating Great Graphs

Charting your course

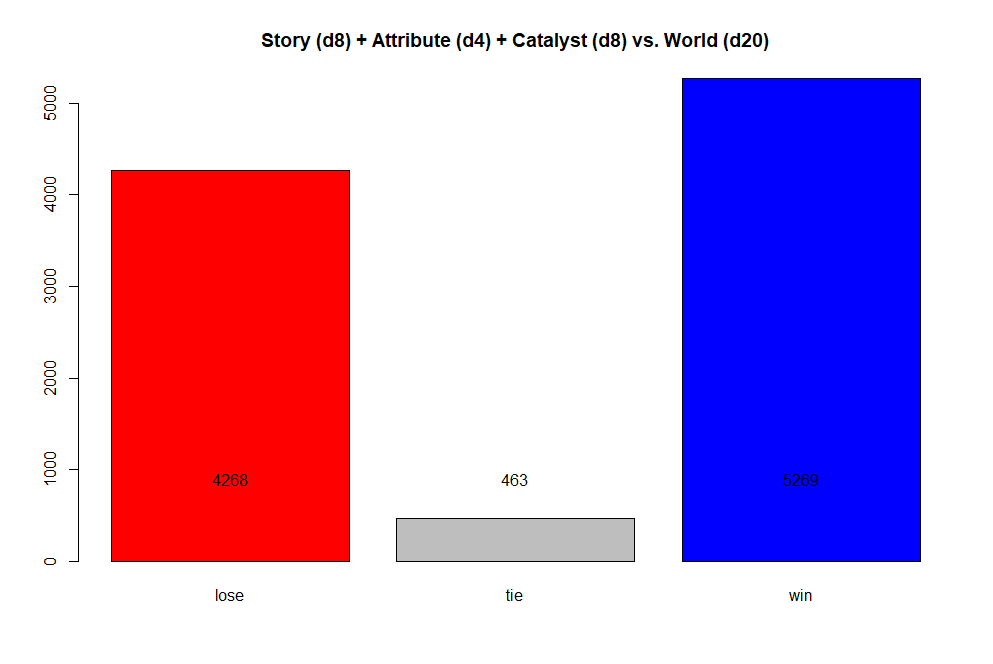

Below is a graph I made for a mentored research project I did a few summers ago. Consider what stands out to you as you look at it.

Looking back on it, I think most aspects of this graph are pretty solid, but I also notice several things I would do differently now. Clearly the graph is about movie theaters and their revenues in the first few months of 2021, but a few changes could help it tell its story better.

So what information turns a graph into an effective storytelling device? In this post, I’ll describe a few graph essentials and show some examples of how to implement them using the framework of my research graph. My hope is that you’ll be better equipped to create a graph that is informative and engaging for your target audience.

Before jumping into specifics, I should point out that a graph should tell a self-contained and complete story. In the event that someone is skimming your article (or that someone pulled your graph out of the article and put it somewhere else), your graph should accurately describe its variables and the setting in which its data were collected.

To that end, ensure that your graph has the following elements: -a descriptive and accurate title. -logical and well-labeled axes. -smart, unobtrusive colors and/or shapes. -a source caption.

Descriptive and Accurate Title

In my view, a title should be accurate first, then succinct. These two are rarely mutually exclusive, but you might need to put a bit of effort into intentional wording to strike the right balance.

In my research graph, I went with “Weekly U.S. Box Office Totals for 2021 (up to May 20),” which I feel is succinct but not quite informative enough. Why? Simply put, “box office totals” is a little vague. Most people will probably assume I mean revenues, which is correct, but it’s definitely possible to find different totals that are also related to the box office - in this project we also studied the number of theaters movies were in at any given week, for example. A better title may be, for example, “Weekly U.S. Box Office Total Revenue, January 1-7 to May 14-20, 2021.” This title conveys all the information the previous title did plus a little more, clearly conveys what the graph is say, and breaks the title into more digestible portions via commas, with a net gain of only one word.

Logical and Well-Labeled Axes

Axes should always have a description. It’s tempting to write a descriptive title and see that as enough, or to create a 0-100 scale and let people assume it’s a percentage. The reality is that axes clear up ambiguity and don’t usually require as much work as a title, so there’s no reason not to include them.

The axis labels in my graph do their job. Week is descriptive enough given the title’s context. Note that my y-axis notes the units of the variable it’s tracking - if you have units, you should always include them on the axes.

Unobtrusive Colors and/or Shapes

Colors make charts interesting and readable; often they can be used to convey even more information within a single graph (such as identifying scatterplot points by another of their variables using differing shades of a color). When using different colors, however, consider two ideas:

(1) Too many colors can make a graph difficult to read. Color should always be used in service of a graph’s readability. If you have two dozen unique values of a categorical variable, the colors assigned to those values may start to look too similar and ruin the effect. (2) Using a color scale alone can limit the information received by colorblind people. For this reason, I suggest also using a shape argument for categorical variables with fairly low numbers of unique values. This way, important parts of your story aren’t lost to a sizeable part of your readership. (Size can sometimes achieve the same effect if your color is assigned to a quantitative variable.)

My graph uses color less for conveying more information and simply for more fun: the movie theater background is thematically appropriate and the green of the text, line, and points makes it readable against that background.

Source Caption

If you’ve made a graph of a data set that didn’t come from your research - or the research that informs the graph isn’t what you’re describing in your article - you need a source caption. This will show readers that you’re not creating numbers out of thin air and will help them trace numbers back to their source in case of further questions or an error on your part (yes, I know you’d never do something like that). Footnote-style citations (i.e. using commas, not periods) are a good idea, although you can probably get away with a webpage title and URL if you’re writing informally.

I took this approach with this graph; it wasn’t intended for publication. That URL was the correct one at the time, but it’s set to always display the current year when you load it up. I’d look a little silly if it weren’t for the webpage title; luckily, you can still easily access the data I was looking at from the URL I added. This is why citation-style is appropriate; it requires you to list the access date of online resources.

Great graphs tell a story - one that usually is enhanced within the body of your article. Using a descriptive title, well-labeled axes, carefully chosen colors, and an all-telling source caption will help you tell your data’s story with style and get readers invested in the rest of your article. Next time you create a graph, consider these four elements and see how they enhance your graph’s readability and style. And if you’ve got graph-making tips of your own, feel free to add a comment so other readers can build their graphs even better.